Is it ‘limerence’? Or is it love in patriarchy?

A viral term offers help to people stuck in romantic obsession, but it also risks pathologizing women's experiences of falling in love in our misogynistic culture.

If you like this essay, you’re in luck, because I have lots more just like it. I’m always taking a critical feminist lens to heterosexual love, sex, and culture. Make sure to subscribe so you get my essays in your inbox each week.

All my essays are free, but paid subscribers get a carefully curated link roundup each weekend. They also make this whole thing possible.

Have you ever obsessed over whether a particular person liked you? Was your aching insecurity temporarily relieved by daydreaming about this person? Did you wait for them to text? Overanalyze their reasons for not texting? Did your spirits soar when they gave you a crumb of attention? Did it crash when they ignored you?

Did you idealize them and ignore their bad qualities? Did you feel short of breath around them? Did you have conversations with them in your head? Did you scrutinize everything you said to them, ruminating on it after the fact? Did your feelings get stronger when things got in the way of your potential love match?

If yes, you might be “a limerent.”

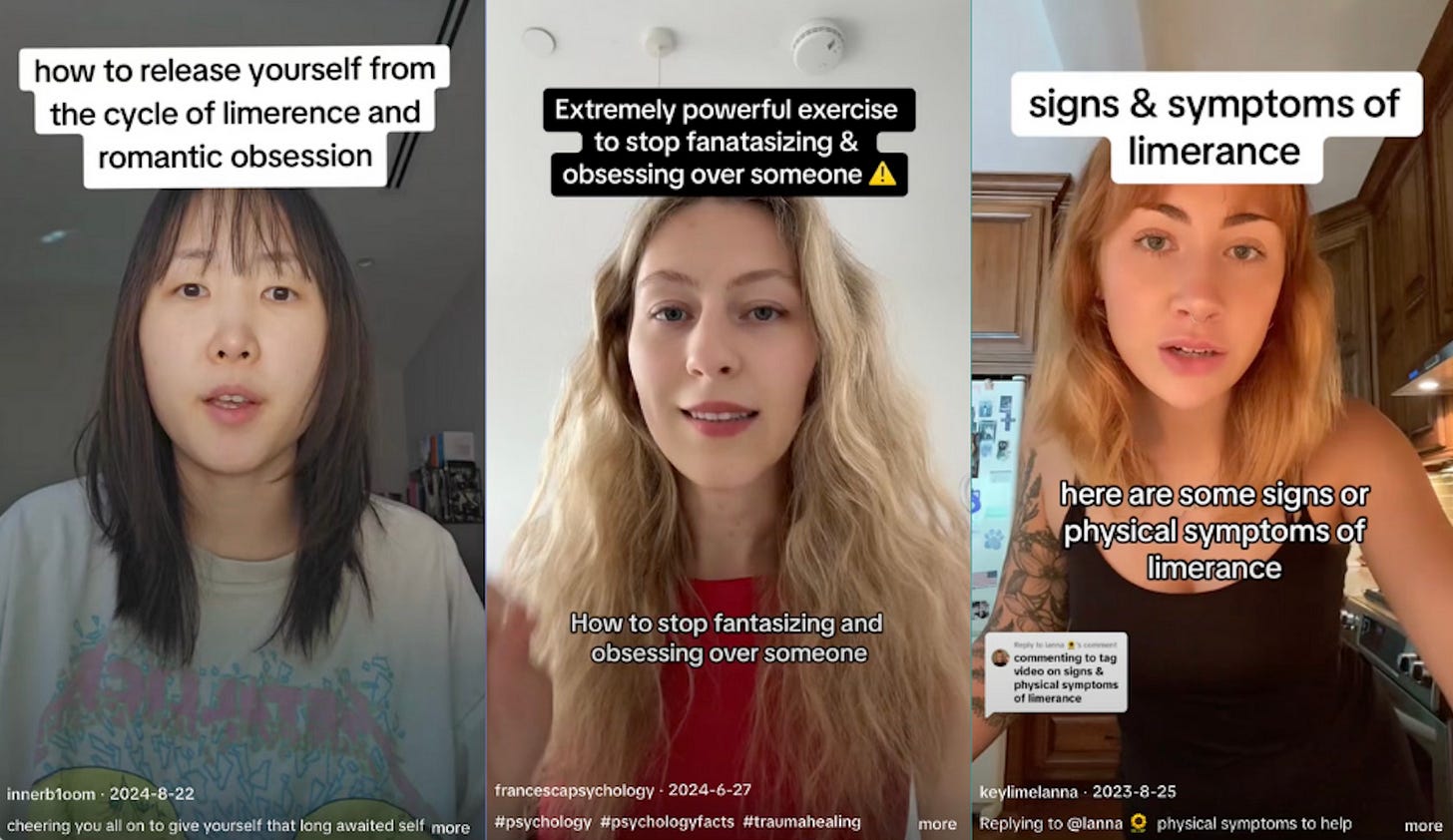

At least, according to a slew of viral videos on TikTok about “limerence.” It’s a psychological label used to describe overwhelming romantic obsession that is often unrequited, filled with uncertainty, and experienced as involuntary and even intrusive. It’s frequently accompanied by “mixed signals” from the “limerent object” or “LO.”

The term, first coined by the psychologist Dorothy Tennov in the seventies, began to surge online early last year. In came the flood of explainers. Just recently, limerence surged in popularity again.

There’s a brand-new book about it, called Smitten, written by a neuroscientist who personally struggled with limerence. In the past couple months, the term has shown up everywhere from Ada Calhoun’s Crush (“We learned the word ‘limerence’… I read definitions of the term as if I were receiving a diagnosis from a physician at a Swiss specialty clinic”) to lyrics in a Lucy Dacus song (“Natalie's explaining limerence between taking hints from a blunt”).

Often, when a viral limerence video has come across my FYP, I’ve had two general categories of thought: Huh, this seems like good and useful advice. Let me save it/like it/share it with a friend. But also: Is there something off here?

My reservations arose in part from the fact that some of these limerence videos seemed to be describing a run-of-the-mill crush. Some videos read to me as detailing the same experience of falling in love as celebrated by everyone from Shakespeare to Nick Lachey on Love is Blind.

The other piece that felt off: the vast majority of these videos were produced by women, often for women. Many cataloged women’s obsessive reactions to what sounded to me like the punishing realities of dating men in a culture that enables ghosting and objectification, fuckboys and Peter Pans. Not always, but often, it felt like these self-help videos were troubleshooting the experience of falling in love in patriarchy.

The actual problem (i.e. patriarchy) wasn’t being addressed—which, fair enough, tough problem to solve—but rather women’s reactions to it. You could say that about a lot of popular dating advice, but these limerence videos, for all their potential helpfulness, also seemed to risk pathologizing women’s emotions. Their hearts and minds. Their passion.

It especially gave me pause because I recently emerged from a deep-dive researching the troubling history of women being diagnosed with hysteria and nymphomania, often for… having emotions and being sexual.

The reality is that limerence is not a mental health diagnosis, despite being frequently talked about as if it were one. It’s experienced by all genders, and by queer and heterosexual people alike, but you might think otherwise if your only exposure to the idea is on TikTok. On social media, limerence often comes across as a straight-lady affliction.

In her 1979 book on the topic, Tennov herself wrote that “the state of limerence is to feel what is usually termed ‘being in love.’” She was downright poetic about it:

Yearned for, dreamed about, and, for the fortunate, reveled in, limerence inspires even ordinary persons to verbal excess. It is called the “supreme delight,” “the pleasure that makes life worth living,” “the experience that takes the sting from dying.” It has been said to power the very revolution of the planet.

The pleasure that makes life worth living! Tennov also wrote that “limerence is love at its highest and most glorious peak,” although she noted that not everyone experiences it.

She found that even those distressed by their experience of limerence were “normal,” “nonneurotic,” and “nonpathological.” Extreme manifestions of limerence, including those leading to interpersonal violence, were “augmented and distorted” by co-occurring conditions, Tennov argued.

Much more recently, researchers have drawn parallels between limerence and clinical diagnoses, including OCD and ADHD. They also note that limerence is poorly studied and understood. Some have tried to draw a distinction between limerence and erotomania, in which a person believes that someone is in love with them, against all evidence to the contrary (see: Baby Reindeer).

But so much of the limerence content on social media just describes straight women’s prosaic dating experiences. “A woman will get love bombed by a guy and feel really strong emotions for him in the beginning and he disappears,” says Charlotte on TikTok. “This woman is very intelligent, she likes a challenge, she wants to win him over … so she obsesses over him… she will wait on him… wait around for hours just to see him for five minutes.”

Hookup and swipe-based dating culture are all about mixed signals and uncertainty, those hallmarks of limerence. Those viral limerence videos describe the experience of nearly every straight woman I knew in my twenties who was in a “situationship” before we had a word for it. Their experience was often the result of encounters with young men’s shitty behavior—objectification, dishonesty, manipulation, entitlement, rudeness, selfishness, and poor communication.

Women are raised on limerence, really. We’re fed sexist romantic myths—the fantasy of The One, the prince. Many of us absorb the desire to be desired—to be seen, to be knit into being—by men. We walk through the world seeing ourselves through men’s eyes.

Compulsory heterosexuality dictates living through men, channeling our ambitions through their successes, realizing our own dreams through romantic and sexual proximity. The Bechdel Test was created because it was so vanishingly rare to come across a film in which at least two named women characters talk about something other than a man.

On TikTok, queer women’s experiences with limerence are particularly illuminating of these dynamics. Niki Christine talks about experiencing limerence toward men before she came out as a lesbian, and she ties these infatuations to compulsory heterosexuality:

Men always felt like this case study… I was trying to figure out why I couldn’t feel the things I saw everyone else feel in relationships. I was obsessively ruminating…Limerence served as my way of trying to be attracted to men and… convince myself that I could be straight.

A similar sentiment is expressed in a meme-based video titled, “Limerence to Lesbian Pipeline,” which reads, “Younger me, obsessed with boys, constant heart breaks, intrusive thoughts about having a one true love. Older me, realizing I’m a lesbian and my obsession with men who didn’t love me was a way for me to stay emotionally unattached.”

If you actually crack open the original text on the topic, you’ll find that Tennov saw women’s experiences of limerence as inextricably tied to patriarchy. She wrote:

Forced to depend on men for status, security, and survival itself, women have been and are still subordinate to men in society. To the degree that social options can mitigate limerent distress, it follows that women are disadvantaged. … The social forces operating on her—and it cannot be denied that throughout modern history they have operated quite harshly—permitted no other role than one in which she required the protection of a male. If love were not a major concern, she might find herself literally left out in the cold.

Limerence has been a survival strategy for women.

Charlotte, the TikToker, gives limerent women the following advice: “You have to do the work on yourself, you have to do the internal work to know that you deserve more than someone who doesn’t want you.” Ah, the want to be wanted. I wrote a whole-ass book about it. Charlotte’s advice is reminiscent of that now-pretty-old saying, “He’s just not that into you,” which may be practically helpful but also fundamentally speaks to the experiences of straight women dating in a culture that hates them.

Speaking of hate, in an article for NPR about Dacus’s limerence song, Ann Powers brilliantly writes:

In a society where queer people must still often negotiate a relationship with the closet—increasingly so right now, as the rights of trans people are on the line and even uttering words like “lesbian” might lead to sanctions—limerence must be viewed not necessarily as a psychological pathology, but possibly as an externally imposed condition.

Limerence requires obstacles. When it’s realized and requited, it tends to fall away into a more stable state of loving. In other words, you’re obsessed, then you get together with your “limerent object,” who becomes much more than an object, and you venture into a mutual relationship. Tennov was clear that limerence often gives way to intimate connection.

What happens when a relationship isn’t intimate? Well, I came across a TikTok video talking about women having limerence for their emotionally-withholding husbands.

Joe Kort, a longtime couples therapist, has tried to normalize limerence on TikTok. “Limerence is a natural state that happens to us when we fall into romantic love,” he explained in a recent video. “The part that’s the problem here is that you have fallen into limerence, or fallen into romantic love, with someone who doesn’t have it back for you—it’s unrequited love.” But it’s also possible that the other person is a narcissist or abusive, he suggests.

In Calhoun’s novel, the married woman protagonist develops an intense crush for a man outside her marriage, after her husband Paul suggests opening up their relationship. Except, whoops, she falls head over heels for this guy who is not her husband, and she embarks on a project of reading everything she possibly can to make sense of these new feelings:

“You’ve read so much”—Paul said, casting an arm out in the direction of my bookshelf, crowded with books about limerence and friendship—“but even you can’t outsmart love. You’re going to the library to try to make sense of something you’re unable, or unwilling, to face in real life—you want each other.”

The protagonist’s emotional experience is troubled by the norm of monogamous lifelong marriage; her feelings don’t fit within the default structure of her life. She tries to outsmart her emotions, but she can’t.

I could point to so much going on in the culture right now to explain the virality of limerence, especially as it manifests in self-help videos for straight women. There’s everything from abortion bans to the political divide between young men and women. Right now, straight love can feel especially star-crossed, in the sense of being hopeless, ill-fated, and overcome by obstacles. Heterosexuality itself is often experienced as an affliction.