Let's think about porn

And ask questions, stay curious, and remember who the 'pro-porn' feminists really were. We can do it! We can do it.

I don’t think that much about porn anymore.

I used to think about porn a lot. It was a big part of my sexual coming-of-age in the 90s and 2000s—something I wrote about in my memoir Want Me. I also spent years and years covering the porn industry as a journalist. I wrote about everything from the logistics of performing squirting in porn to the ways Instagram was exposing performers to harassment and financial exploitation.

A while back, I stopped reporting on it—slowly at first and then altogether. There’s much more to it than this, but the simplest reason is that I developed other journalistic obsessions. Recently, though, I found myself thinking about porn again.

Something really is in the air.

Last week, The Atlantic ran a book excerpt from Sophie Gilbert’s Girl on Girl arguing that internet porn—along with popular music, TV, and fashion—negatively impacted the generation of women who came up in the same era that I did. The headline: “What Porn Did to American Culture.”

Then, over the weekend, I noticed a viral Substack essay headlined, “Sex work will never be feminist,” which creates quite a straw man of sex positivity.

Also, the “anti-porn” feminist Andrea Dworkin—whose work I find totally brilliant even as I disagree with large swaths of it—is experiencing a resurgence with Gen Z. (Then again, so is the “anti-feminist feminist” Camille Paglia. Interesting times.) Dworkin's Pornography was recently reissued, along with several other of her books.

This follows years of growing critiques of sex-positivity—both by clear-eyed feminists looking back at the neoliberal cooptations of the movement, as well as by right-wing reactionary feminists who seem to wish us all back in the kitchen.

The loudest anti-porn voices right now are probably Republican politicians, who are attempting to censor it in various states—to say nothing of Project 2025’s vision of an outright ban. The loudest pro-porn voices right now are also probably Republicans—more specifically, MAGA cult members, who are proudly celebrating the existence of big boobs and the objectification of women as an anti-woke “gotcha” against liberals.

Months back, I wrote that we are “in the midst of a resurgence of right-wing erotic nostalgia not just for the 1950s housewife but also a pre-MeToo era of unapologetic objectification.”

That is the same era and phenomena that are the heart of Gilbert’s book.

Back in 2008, when I was 24, I tried to sell a proposal for a book titled, “Generation XXX: Growing Up Female and Feminist In the Age of Porn.” I got an offer that in retrospect was actually pretty good, but not good enough to quit my full-time journalism job in order to be able to actually write it. I am very glad that I didn’t write that book.

I wasn’t yet clear on what it meant to grow up “female and feminist in the age of porn,” because I was still growing up. I did include this line in the proposal, though, which I still stand by: “We are trying to act the part of the sexually liberated within a culture that isn’t sexually liberated. Is it really any surprise that there are some troubling contradictions in our behavior?”

I was reacting in part to Ariel Levy’s book Female Chauvinist Pigs, which had come out years earlier with a big splash, arguing that my generation of women represented a “new brand of ‘empowered woman’ who wears the Playboy bunny as a talisman, bares all for Girls Gone Wild, pursues casual sex as if it were a sport, and embraces ‘raunch culture’ wherever she finds it.” That book enraged me at the time; I felt that her critique was mocking and lacked empathy.

Now, setting aside some of its shortcomings, I see it as having aptly captured evidence of the neoliberal co-optation of sex-positivity, which turned “empowerment” into an individual project. So much of what she was zeroing in on back then is now being unpacked in Gilbert’s book, which is a very smart and impressive synthesis of 2000s-era misogyny.

I also think it’s at times too simplistic in its attribution of blame to porn, which she suggests is the original source of so many of the other phenomena that she writes about in TV, music, and fashion. I think the tentacles of patriarchy suggest much more complicated routes of influence. And yet I agree that porn—as with other forms of commercial media like, say, reality TV—can have a profound influence on our brains and bodies and sex lives.

I have found myself asking, again and again over the last week: What was porn’s impact on me, personally? I have a different answer each time.

Porn’s imagery—alongside the influence of so very many facets of mainstream culture—contributed to my having sex throughout my twenties that was often rote and performative and lacking in pleasure (for me). In some ways, porn alienated me from my own desires, because I approached it as a way to become an expert in men’s desires.

It took a long while to escape my false assumptions about what porn was (i.e. that it was a guidebook to hot and pleasurable sex, and a straightforward and literal accounting of what straight men wanted). And I escaped those false assumptions in large part by writing about the porn industry full-time as a journalist—not exactly an easily replicable route of self-discovery.

On the other hand, man, I love porn.

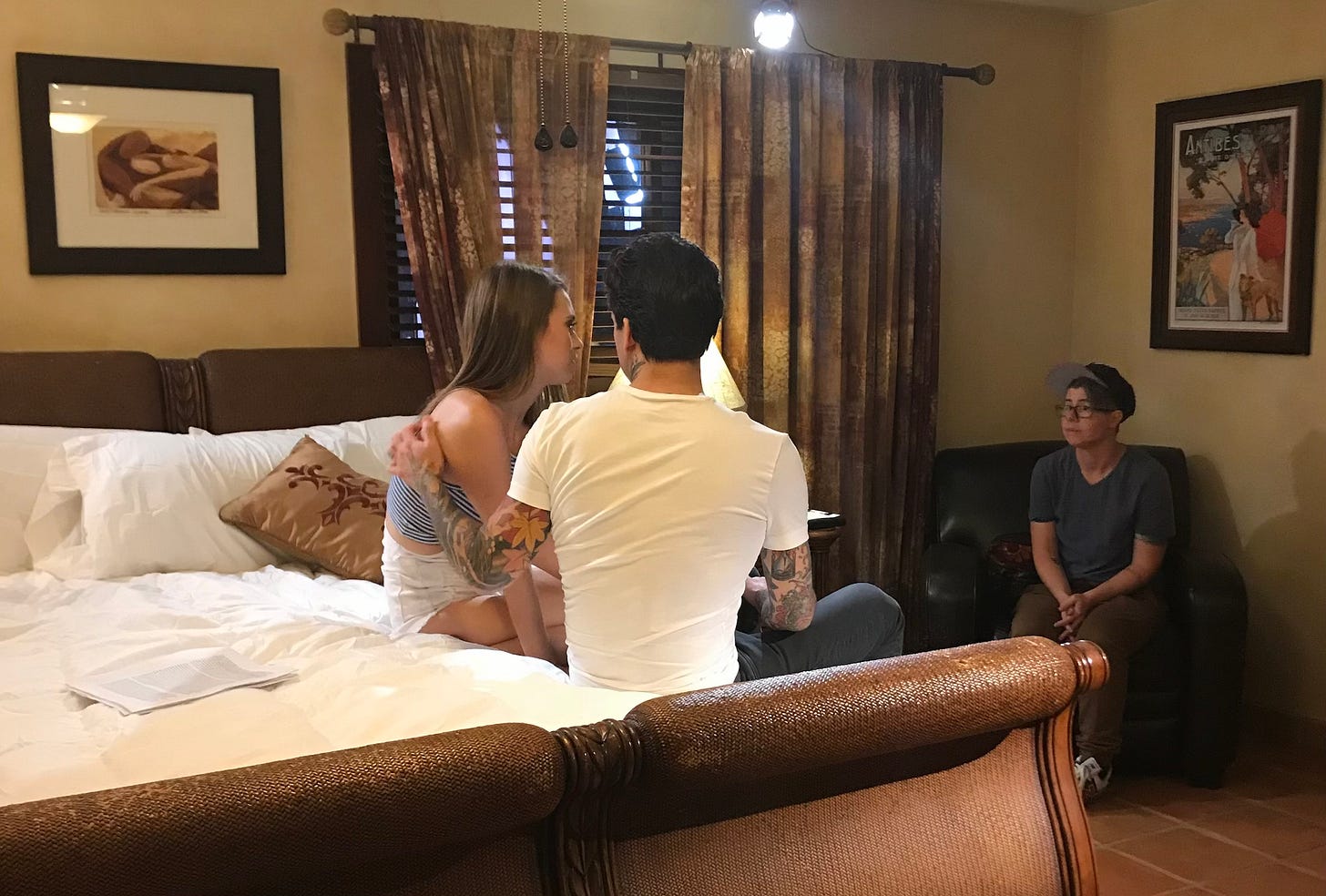

I don’t watch it anymore, at all (partly because reporting on the industry killed my ability to escape into the fantasy of it, and partly because… I now prefer my own mind). I love what it once meant to me, though, especially as I ventured into indie and queer porn. It unlocked a world of possibility, exploration, and fantasy. Years back for the Guardian, I wrote about this period of discovery:

I latched on to women performers who portrayed sex as a weird, messy and sometimes deeply un-pretty affair. It was a model for what mutually attentive and enthusiastic sex might look like. But they also played with power dynamics, moving between submission and dominance. It felt to me like cathartic drama.

Men and their desires had been the focus of my amused, occasionally horrified attention, but now I was riveted by my own. How many different doors could I walk through? What dusty, dimly lit rooms might I discover? I’d taken the master key and was eager to unlock every hidden corner.

I added:

Sex could be creative, fun and theatrical, it turned out. … Every act was embedded with social and political meaning, and porn let me examine that meaning from a safe and comfortable distance.

Back then, I faked almost all of my orgasms with my partners. I didn’t fake any with myself and my laptop, you know?

I have plenty of critiques of porn. So many of the later articles I wrote about porn were critical—of everything from alleged on-set abuse to some of the essentializing ideas behind “feminist” porn to popular sub-genres with capitalistic fantasies.

You’re also unlikely to find many people who are quite so earnest in their positive feelings about porn. I always felt like my critical analysis was an act of love—for porn, for sex. For the potentials of both.

So many conversations happening over the last few years make it feel like the Sex Wars never happened, or like no one remembers.

was the first person I vented with about that “sex work isn’t feminist” piece and, thankfully, she’s now fully unpacked the issues in that essay, as well as in these broader cultural rumblings. She wrote:I’m afraid that what I’m seeing is simply reinventing the wheel of a battle that hasn’t gotten us a world without sexual violence. The antiporn feminists will blame this on the proliferation of pornography and the negative aspects of sex positive culture. Both the changing shape of porn and the problems with shallow sex positivity are important to grapple with, but to point to these things as the root cause of harm is too simple—and it puts sex workers in more danger.

Some of the biggest pro-porn—or anti-censorship—feminists were actually highly critical of the medium. They were also full of curiosity and questions—about desire and fantasy and power. The anti-porn side often tended to offer “answers, albeit simplistic ones,” as the legendary film scholar Linda Williams put it.

I recently revisited Williams’ work in the wake of her death last month. She was known for the 1989 book Hard Core, which took porn seriously as an entertainment medium worthy of analysis, in part as a response to the anti-porn rhetoric of the Sex Wars. Williams both argued that pornography “offers exemplary symbolic representations of patriarchal power in heterosexual pleasure,” and also that “in filmic hard-core pornography, the ‘self-evident’ is not as self-evident as it seems.” There is “complexity involved in reading sexual acts in hard-core films,” she argued.

Let’s keep the complexity and curiosity alive. Let’s remember.

So much to say about this!!! Firstly, I was one of the people interviewed for Ariel Levy’s book and I still have nightmares about that interview. I can’t believe her chapter on bois has not garnered huge criticism at this point as being anti-trans. I think she was uninterested in the theoretical ideas behind exploring how our culture positions “women” in the sexual landscape and that she had a lot of biases going into the book that she didn’t reveal - namely thinking that because our culture is so sexist, we shouldn’t claim to have any curiosity within in.

Also so much to say about porn but mostly would just use it still as an argument against the “men are more visual” than woman statement that is massively wrong but still prevails.

SO WELL SAID. Forever admiring the clarity of your writing/thinking. (& I was so riled up, I totally forgot to include the Gilbert, really appreciate your engagement of that piece here).