What even is love?

Considering the possibilities of 'fleeting intimacies,' erotic friendship, undefinable obsessions, and the radical potentials of sex.

Just a glance from a “fetching man” on a subway train would send Manuel Betancourt into “hypothetical rabbit holes” where he imagined “a conversation that would lead to a number, to a date, to a future,” he writes in Hello Stranger. Similarly, writhing against a hot guy on the dance floor of a Chelsea bar—amid disco balls, go-go dancers, and “salt-tinged kisses”—he felt pulled toward the idea of this stranger being his “perfect match.”

Having grown up on telenovelas and rom-coms, he felt “ill-equipped to imagine any other use” for such encounters. He couldn’t just enjoy these “fleeting intimacies,” Betancourt explains. A bar hookup “was the start of a story, not a narrative in itself.”

In Hello Stranger, a mix of memoir and cultural commentary, he resists that narrative pull, though. Betancourt tosses out the romantic script. What would happen, he asks, “if we let ourselves inhabit that moment of longing where everything and perhaps nothing is possible,” “if we “stretched it past its breaking point” and lived in uncertainty?

As part of this investigation, Betancourt writes about everything from cheating in a prior marriage (affairs offer “a peek at the stranger within,” says Esther Perel) to ending up in a non-monogamous throuple. He also investigates the “transient intimacies” of cruising. It’s “a different way of looking, a queer mode of reading, an example of impersonal intimacies, proof of a new vision of sociality,” he writes.

Hello Stranger is just one of a handful of recent books—ranging from an indie memoir to an activist handbook to an academic treatise—that deconstruct the usual stories around sex, romance, and love. Instead of a single prescribed narrative arc, they offer up a profusion of possible paths. Many of these paths are defined less by a set destination than a question mark.

What if we’re more ourselves with strangers than inside “the rotting roteness of long-term intimacy”? What do we call an unreciprocated romantic (but not sexual) love? What if we thought of eros as flowing through friendship, nature, and art?

At their most optimistic, these books envision sex and love as bringing about vital knowledge and changing us, as connecting us to the world as it is, but also potentially having the power to revolutionize it.

In Elseship, Tree Abraham documents her obsessive and unrequited love for her roommate. She experiences a romantic narrative pull, but not toward quote-unquote consummation. Her sexuality is “not a solid shape,” she writes. “And in the seldom instances where I feel a simmering physical attraction to another, it is always a combination of things, and never exclusively or dominantly sexual in form.”

She’s tried on all sorts of labels—bisexual, sapiosexual, asexual, biromantic, demisexual, and queer—but there aren’t enough to “encapsulate the qualities that might attract me to another person.”

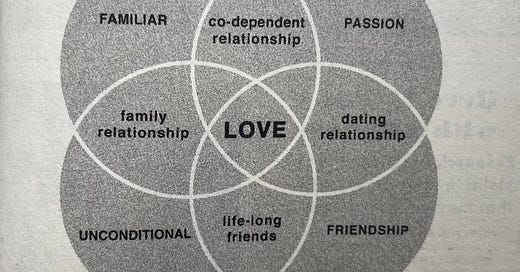

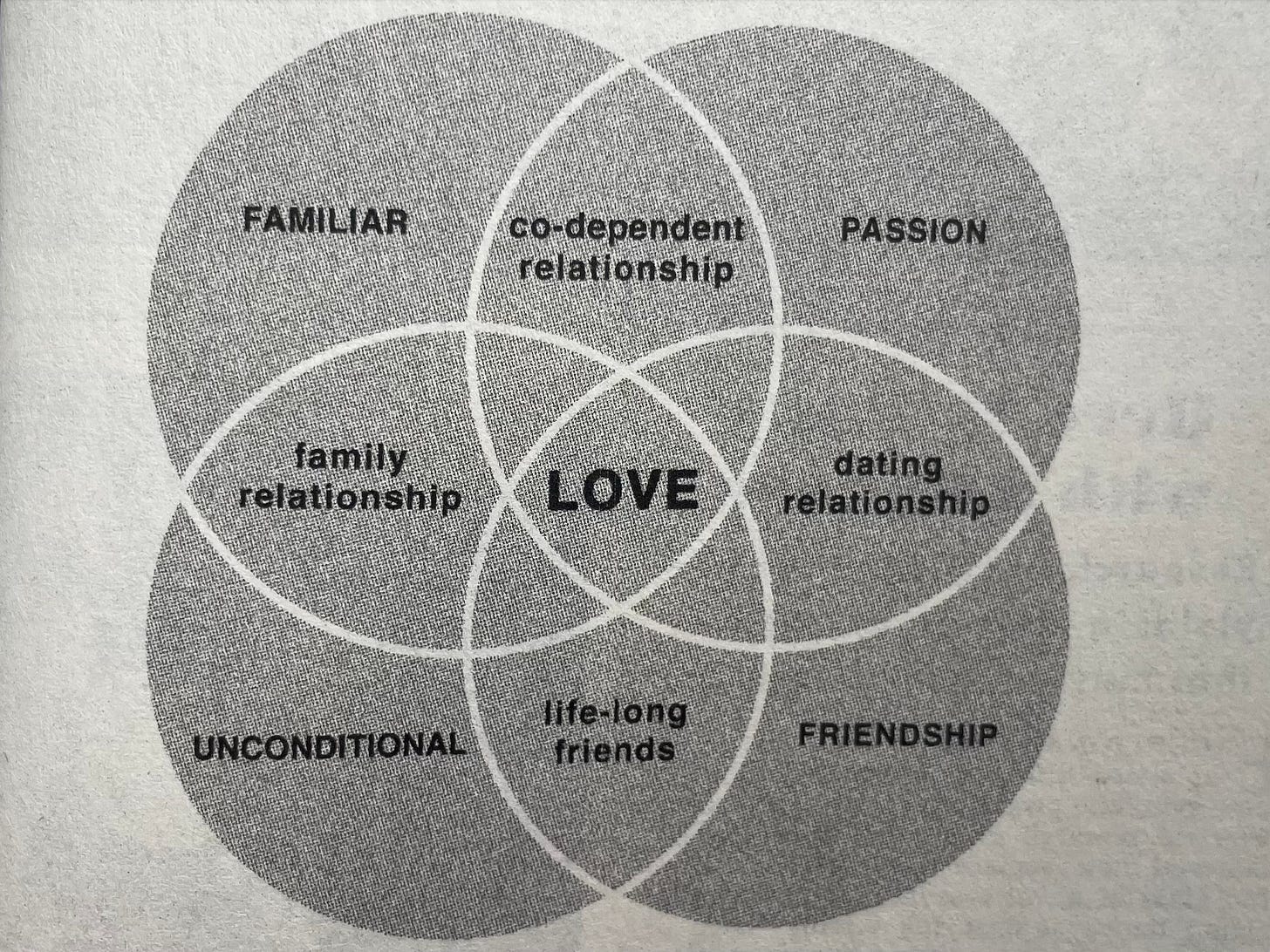

Here, we get a look at love with sex taken out of the picture, but we also see the difficulty of trying to define love without sex. The usual labels and scripts do not apply. The book is filled with sketches and collages that attempt to sort out the seeming illegibility of her feelings, which really serves to highlight the absurd simplicity with which we typically define love.

A Venn diagram shows four overlapping circles with an all-caps “LOVE” at the very center and an assortment of categories: “familiar,” “passion,” “unconditional,” and “friendship.” Abraham writes, “Automatically I want to smush the disparate parts into some sort of figurative Silly Putty.”

What a thrill, the idea of smushing it all together and just seeing what happens, right? Collapsing all those false and controlling borders, embracing a little chaos.

Federica Gregoratto’s Love Troubles is a rigorous academic examination of eros—ranging from Plato to Sally Rooney—but the further it pushes into love, the more love feels like that smushed Silly Putty. Who could say what its exact boundaries are?

Gregoratto, a philosophy professor, writes of “erotic bonds” between people who are “just friends” and “relationships that occupy a middle space between friendship and romantic love.” These middle spaces make “the conceptual distinction” between friendship and romantic love “lose its significance and power to organize social relations and practices in general,” she writes.

Similarly, the very concept of a “stranger” is troubled by Betancourt’s experiences with “ephemeral intimacies” that in some ways offer up an authenticity and freedom that he found lacking in long-term relationships. He writes:

A stranger can offer us the chance to see ourselves anew. To imagine a different way of moving through the world. Every chance encounter, I’ve come to find, can be a chance to remake yourself. The unguarded intimacy that’s nurtured in moments when we meet strangers we’re enthralled with offers infinite possibilities to be better versions of ourselves. But also, maybe, to be and project the person we’ve always known ourselves to be.

Erotic love—as the feminist poet Audre Lorde taught us—can be “a form of deep, passionate connection between persons (but not only: it is also a connection with oneself, and with the world, through various media, artistic in particular),” writes Gregoratto.

I find myself asking: What isn’t love? What isn’t eros?

Desire itself reveals the falseness of our romantic labels. Writing of Walt Whitman’s poetry, Gregoratto notes that “it is the force of the body that somehow imposes itself on us and makes us realize that the forms in which we have organized our intimate lives, and our lives more generally, are deeply flawed and need to be revised, precisely in order to let this desire freely flow.”

There is wisdom in our wanting.

In Love in a F*cked-Up World, the activist Dean Spade makes a connection between social justice and the need to topple the romantic myth. Spade argues that these scripts redirect our desires away from more radical aims. “We are supposed to limit our marvelous capacities for connection and care to the confines of the romance myth,” he writes. “We are not supposed to find each other, to build deep relationships that transform us, to destroy racial capitalism, and to collectively restore and create liberated ways of being together.”

Gregoratto enumerates the many common exploitations of love—particularly for women in heteronormative relationships—but also maintains a utopian sense of possibility. Not inevitability but possibility, theoretically. She suggests that we look for lessons in “the perturbations, disturbances, frictions, and ruptures that arise in the liminal passage between norms, structures, and rules of love and what exceeds them.”

In other words: Where do things spill over? And what do those spills, that excess and abundance, teach us?

All of these books, in their own way, reach beyond the so-called private sphere of love. They are both interested in individual pleasure and satisfaction, but also something broader and more collective. “From within our social situation,” writes Gregoratto, “love can operate as a movement or gesture or resistance or opposition, an internal fracture from which critical and transformative energies can be unleashed.”

She quotes the philosopher Theodor Adorno: “If love in society is to represent a better one, it cannot do so as a peaceful enclave, but only by conscious opposition.”

What does that mean, though, in practice? What does that look like? Of course, there is no one answer. Betancourt offers a glimpse of cruising and throupledom and the delights of dwelling in the unknown. Abraham opens up an uncertain smushed-up space that vibrates with intimacy and connection. Gregoratto surveys the landscape of recent and emerging romantic labels, like polyamory and relationship anarchy. And Spade gives practical advice around everything from avoiding romantic projection to embarking on “revolutionary promiscuity.”

What is most compelling across these books, though, is this value of shared discovery, as opposed to a set individual, or coupled, destination. As Gregoratto puts it, “Eros can become a space of education in which friends and lovers develop and refine virtues, capacities, and knowledge that apply not only to themselves but also to the world they inhabit together.”

"What does that mean, though, in practice? What does that look like?"

Exactly. Trying to figure that out. On the outside, it looks like I'm "Mother" in my nuclear family, but taking into consideration my sexual identity and endeavors, I have friends that don't exactly fit into the "friend space." (There's a lot of spillage, if you will, and not necessarily sexual.)

Great recommendations, especially interested in the Betancourt read.

Thanks, Tracy.

I loved this, thank you for this thoughtful synthesis! (I am also writing about Dean's book this week, of course lol).