What is 'Pedro-masculinity'?

It's the antithesis of ugly and aggressive petro-masculinity, sure, but it's also another narrow box. Let's not reduce Pedro Pascal's goodness to 'masculinity.'

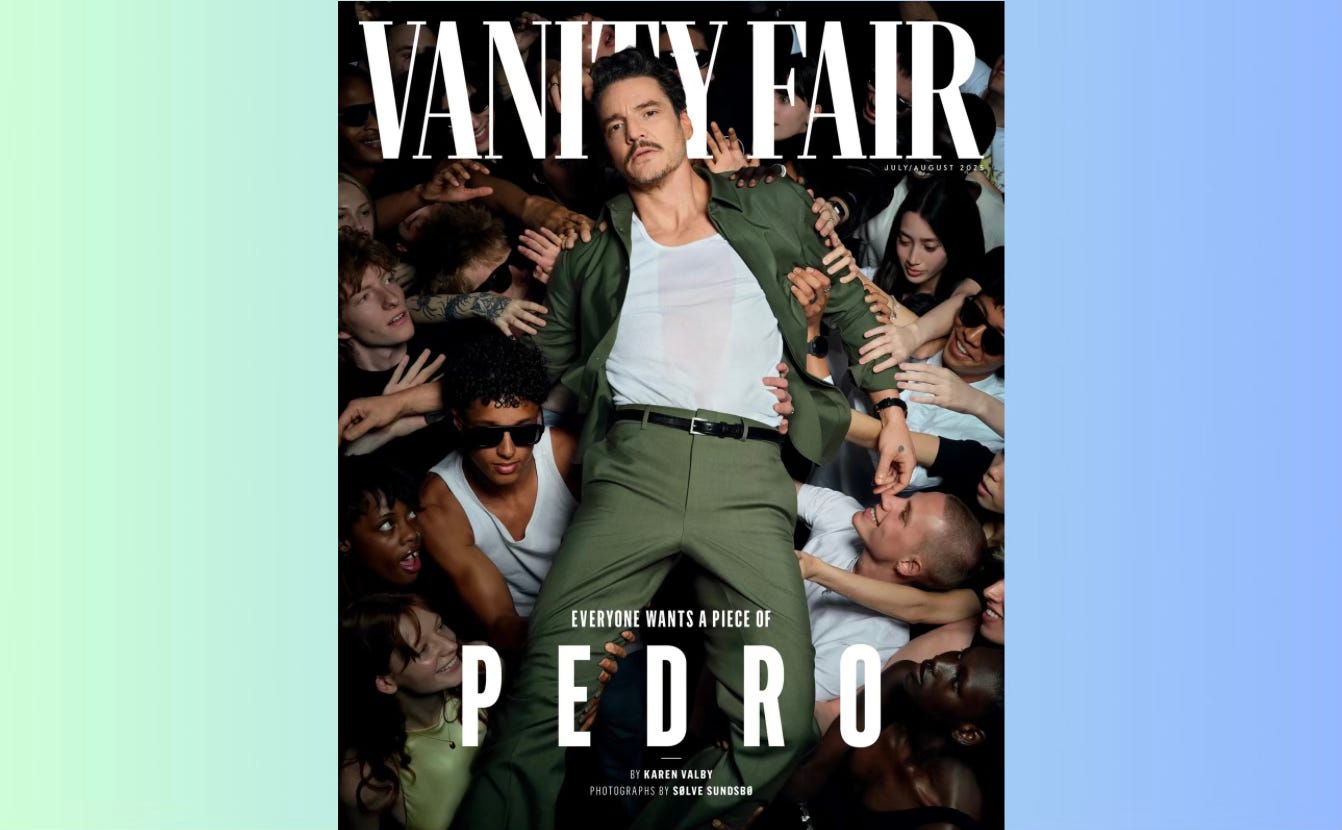

Pedro Pascal is on the cover of Vanity Fair this month, held up by a sea of hands—almost like he’s crowd-surfing at a concert. The headline: “Everyone Wants a Piece of Pedro Pascal.” One of the promo videos for the issue is a closeup of his face with multiple pairs of hands rubbing and pawing at his head.

The frame of the article itself is that everybody loves Pedro—except for maybe J.K. Rowling and other shitheads. Tucked into the piece, though, is another contention—not just that everyone likes Pascal, but that everyone likes him as a man.

Spike Jonze, who directed Pascal in his joyful ad for Apple AirPods, is quoted as explaining the actor’s popularity like so: “I think that he’s what we want in masculinity.”

I’m always fascinated by the ways that people talk about masculinity—say, trotting out the term “positive masculinity” when a man exhibits a balance of traits stereotypically labeled as masculine and feminine, or else emphasizing widely respected qualities like “honor” and “courage” as somehow uniquely belonging to the domain of men.

I found myself wondering, in a tongue-in-cheek way: What is “Pedro-masculinity”? Which immediately made me think of “petro-masculinity,” that version of manhood that is reliant on fossil fuels, racism, misogyny, and authoritarianism. Pedro-masculinity feels antithetical to all that, but what exactly is it?

Jonze doesn’t elaborate on his theory, but journalist Karen Valby tries to on his behalf:

It’s not just about how rugged and alive Pascal is onscreen. It’s also his cheeky fun with fashion… It’s how he bopped to Devo at the SNL50 concert. It’s how he publicly celebrated his younger sister, Lux Pascal, when she came out as transgender in 2021 and remains a passionate advocate of the community.

Rugged and alive. A cheeky, fun fashion sense. Bopping to Devo. Advocating for the trans community. All of these things evoke a feeling that the rest of the piece fleshes out more fully, although never explicitly in terms of masculinity.

We hear about Chelsea Handler calling 2023 “the year everyone became horny” for Pascal. The piece cites that New Yorker cartoon where a therapist tells a client: “It’s not strange at all—lately, a lot of people are reporting that their faith in humanity is riding entirely on whether or not Pedro Pascal is as nice as he seems.”

At one point, Pascal tears up and clasps Valby’s hand in a moment of bonding over their shared losses of their mothers to suicide. Actress Sarah Paulson, his longtime friend, tells us about the “well of pain that lives right behind his eyes that he’s never tried to hide from.” (Ah!)

We hear about how as a child he wept while watching The Color Purple. “For the rest of fifth grade, he carried a copy of Alice Walker’s novel around like it was the Bible,” writes Valby. As a teenager, he connected with James Baldwin’s writing.

He takes his interviewer to a Palestinian restaurant and explains that he thought it would be fun to share some small plates, but Valby notes, “He’s posted more than once on Instagram about what’s unfolding in Gaza, so I suspect he’s also making a statement of support by doing an interview here.”

Other details: a recent party he threw in London, where he “hired Honey Dijon, a trans woman and divine Grammy-winning DJ and fashion icon. He wore a black nylon 4sdesigns overcoat over a Protect the Dolls T-shirt, and his friends spun him around the dance floor on their shoulders.”

In other words: he’s hot, nice, emotionally open and attuned, deep-feeling, artistic, a reader, a dancer, stylish, an advocate, and politically right fucking on.

The article alludes to ongoing fan speculation about his sexuality—referring to how Pascal doesn’t talk about “his own personal life in the press”—and thankfully Valby doesn’t push or prod on this front. Maybe the sexual and romantic ambiguity is part of what Jonze is referring to—this isn’t an aggressively and rigidly defended hetero-masculinity.

I think another way of putting all of this is that Pascal comes off as a lovely, soulful, and multi-faceted… human being. In the past, I’ve argued against notions of “positive” or “tonic” masculinity. Last summer, I wrote about Tim Walz being held up as one such model, thanks to his being seen as having “traditionally masculine traits that are associated with strength and toughness, along with feminine-coded traits of care and compassion.”

I argued that insisting on masculinity—even the “good” kind—“keeps boys and men and everybody trapped in a box,” and wrote:

We should be aiming beyond masculinity—or, perhaps, deeper than masculinity. What are some positive, inspiring, and exciting models for being a person in the world? What if some of those models for boys and men actually came from women?

Granted, I think that Pascal’s human-ness, and humane-ness, in this time of aggressive petro-masculinity is often experienced most saliently as redemption for masculinity and/or the potential of men. It’s like that New Yorker cartoon—maybe it feels, if we’re to put it in the most absurdist terms, not just like a faith in humanity, but also masculinity, or men’s potential, is riding on Pascal.

Thanks to

’s comment on a recent newsletter, I wonder, too, if it feels to some like he’s vaguely restoring faith in heterosexuality, too. He did just star in a summer rom-com opposite Dakota Johnson, in which he was cast as a “unicorn” of a man—the exception to the rule.All of this risks cheapening his seeming goodness—or co-opting and re-purposing it for questionable aims. When a man’s masculinity is celebrated in this way, it’s often intended as progressive and yet I find it fundamentally regressive. It’s typically a celebration of a man who is seen as successfully executing a balancing act of traits without tipping too far over to one side. Like I said back in August: “The Walz model is compelling because he still reads as masculine,” despite his supposedly feminine traits. What would be said of Pedro if he couldn’t both pull off denim short-shorts and killing zombies on TV?

A celebration of Pedro’s masculinity is maybe a challenge to petro-masculinity, but it’s still too narrow a frame. I don’t think we want to stuff anything—whether a person or our faith in humanity—into that box.

I love this take. You are absolutely right that in all of this effusive praise for Pedro Pascal's masculinity (or "Pedro-masculinity"), many people are still trying (without acknowledging or even realizing it) to construct their ideal "man box," and laud Pascal as an exemplar.

When we step back and examine this phenomenom, we can see many implicit assumptions at work. First, the assumption that aside from his good lucks, his mix of emotional traits, and the overall way he engages with the world is extraordinary--- "normal" men fall short of this standard.

Also-- even though Pascal doesn't talk publicly about his sexual orientation or gender identity (or insofar as I know, publicly identify as something other than a cisgender heterosexual man) many people proceed from the assumption that he is cisgender and heterosexual - and those assumptions are indeed factored into the final "grade" we award him (A+!!!) as "a man."

We should assume nothing. When we assume someone is cis and "straight" unless they take it upon themselves to tell us otherwise, we reflexively invoke the first basic rule of heteronormativity. If we then unconsciously proceed to factor in other assumptions (most men are more like "x") then what pops out of our mind in the end is "what an extraordinary man!"

Perhaps the real reason so many people hold Pascal in such high regard is because he presents himself, and appears to live, as a fully realized *human being*, who exhibits many of the traits we value (or should value) in *all* people-- regardless of how they may (or may not) self-identify as part of any particular "tribe."

“Bopping to Devo” is an amusing image. I’ve never thought of Devo in “that” way.