The erotic 'we' could change the world

On utopianism and new possibilities, now and for the future.

I mean, to be honest, I’m writing this while yelling at my kid.

OK, “yelling” is definitely too strong a word. I suppose that using that word in a public venue is really just a way of yelling at myself. A public self-shaming. This is more accurate: I’m slightly raising my voice so as to be heard in the other room. Just begging for a little time. “Please, honey. Please help me.” Because my kid has the week off school.

There are so many weeks off school.

This negotiation with my kid felt unbearable until I just now recognized it as such. Now it’s just very funny for being so untenable. A child with no school! Two parents with work to do! Ha ha ha. Hilarious.

Later, I’ll hand off childcare duties and switch to fact-checking my book, a task that feels so formidable it’s a little hard to breathe when I think about it, but otherwise I would be paying thousands of dollars for someone else to do it, which would also make it hard to breathe, for money reasons and letting go of control reasons.

Fact-checking is deeply unglamorous work, but it also feels weirdly holy to comb through my own words and highlight every checkable assertion of fact in red and then prove to myself that it’s accurate. Some of it is silly and small. I was 24 in 2008. It was sunny on that day in 2022.

I’ve already found a couple handfuls of the tiniest factual errors that probably no one would ever discover in the final book, but I’m combing through and picking them out like little nits and it makes me feel a little less itchy, you know? Because I’m taking great care of this book.

What about your child? asks an accusatory voice inside my head. Look, I’m doing my best. We just got back from a three-day “vacation.” It was lovely and hard. There were big prosaic swaths of parental exhaustion dotted with fierce, fleeting moments of the sublime—like, hiking in the woods to stare up at a 1,400 year old tree, but alongside calls of I’m bored, I’m bored, I’m bored.

At the end of one day, C. and I paused to look at each other—overwhelmed and exhausted—to say what the fuck with our eyes. The what the fuck wasn’t about our kid but rather the circumstances. We both really needed a vacation from work, but, of course, parenting is also work. Family vacations can feel like doing an impromptu shift as a camp counselor. It can make work look like the vacation.

Now, back at home, it’s work-work alongside the work of parenting.

Here’s another funny thing: the stack of books currently on the table in front of me in the midst of this untenable-ness: The Utopia Reader, Everyday Utopia, Mutual Aid, Heaven is a Place on Earth, Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism, and Abolish the Family. These are books about how we organize our lives and how our lives are organized for us. They are about who and how and what we love.

I seem to go through life collecting new obsessions and then assembling a related curriculum and reading list for myself. This latest obsession could be called “utopianism,” although C. recently offered up an addendum: “and new possibilities.”

Utopianism and new possibilities.

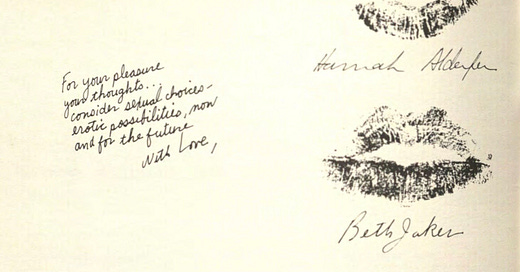

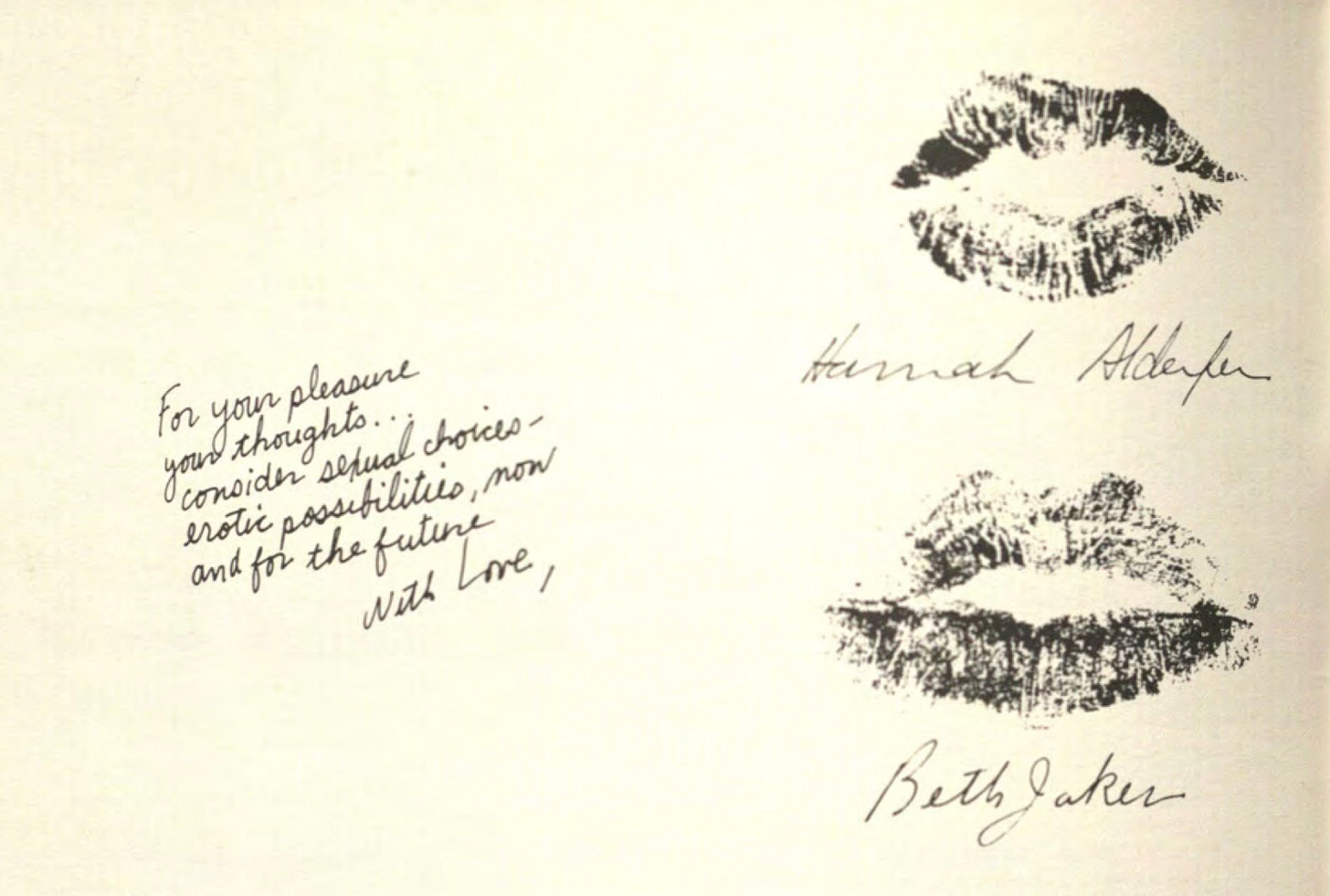

The last part was inspired from this framed piece of art we have in the house. It’s a two-page spread from Diary of a Conference on Sexuality, a zine that emerged from the legendary 1982 Barnard Conference on Sexuality, where feminists got together to talk about sex, pleasure, fantasy, and politics. The framed pages feature a handwritten sign-off from the zine’s creators, along with their lipstick-ed smooches. It reads:

For your pleasure

your thoughts...

consider sexual choices—

erotic possibilities, now

and for the future.

We have that framed in our little suburban-adjacent nuclear-family home, our sphere of married, monogamous, and hetero parenthood. The sketch of our shared life is very basic, very conformist, but it doesn’t always feel that way, mostly because we talk about things—like, say, jointly coining my new obsession as “utopianism and new possibilities.”

There’s always a little gleam of what if. A possibility of new possibilities, not just within our relationship but out there in the world. Especially out there in the world.

After writing last week about those new books on love, I keep coming back to this idea that appeared in Federica Gregoratto’s Love Troubles, which defines love and eroticism in the broadest of terms. She talks about the sense of an “erotic we,” between lovers, friends, activists, or neighbors, whatever the case. They “make love, converse, act together, and undergo affects they do not entirely grasp,” she writes, and come to “figure out crucial things about themselves, and about the world in which they live.”

It all hinges on that sense of a “we,” which might start with a connection between just two or a few people but eventually ripple out beyond them. Through that ripple, Gregoratto argues, the erotic we could change the world.

As I turn to my big project of provable facts—of what is or has been—it seems perfect to leave you on that note of dreaming and possibility.

Well said. I would say that "protopian" is probably a better term than "utopian", as the latter literally means "no place" in Greek, and there is a long history of people seeking to create utopia and making the perfect so much the enemy of the good that they end up creating dystopia. Otherwise, this article is 🔥🔥🔥

Hopefully, you will answer the question "Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism" .

;)