If you like this essay, you’re in luck, because I have lots more just like it. I’m always taking a critical feminist lens to heterosexual love, sex, and culture. Make sure to subscribe so you get my essays in your inbox each week.

All my essays are free, but paid subscribers get a carefully curated link roundup each weekend. They also make this whole thing possible.

I’ve been thinking about this concept of hetero-exceptionalism.

I’m envisioning it as a variety of heteropessimism. It’s a perspective that recognizes that heteronormative love and sex can be punishing for women, while emphasizing exceptions (happy heteronormative relationships) that are attributed to men who are unicorns or women with discerning taste and romantic savvy. Crucially, it comes along with a sense of blame, specialness, and superiority, as opposed to solidarity.

It is part traditional romantic fairytale around The One and Prince Charming, and part neoliberal feminism with its focus on individually navigating systemic oppression (in other words: getting yours within patriarchy).

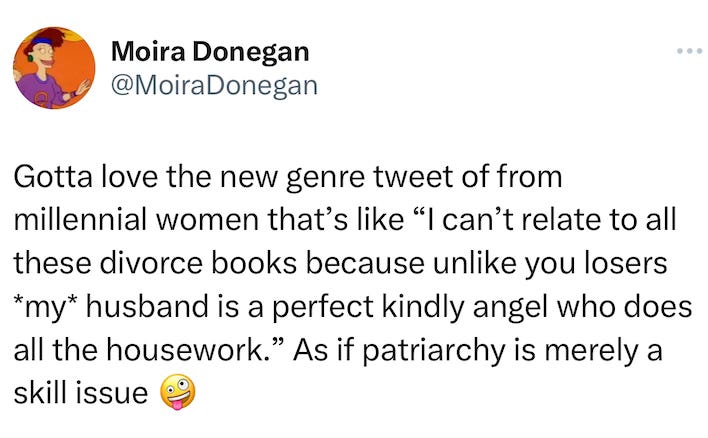

I’ve been thinking about this concept in part because I came across this from Moira Donegan:

Gotta love the new genre of tweet from millennial women that's like “I can't relate to all these divorce books because unlike you losers *my* husband is a perfect kindly angel who does all the housework.” As if patriarchy is merely a skill issue.

I haven’t personally observed this genre of tweet as it relates to divorce memoirs, but I think there is some of the feel of it in parts of Parul Sehgal’s recent review of Sarah Manguso’s Liars, which discounted the novel’s take on the cultural coercion around marriage and questioned the protagonist’s culpability in her marriage’s demise.

I interpret Donegan’s point (and agree with it) as such: personal happiness within a marriage doesn’t negate broader systemic problems, and no relationship actually remains untouched by the influence of those systemic problems.

I’d add: a happy marriage is not a solution to systemic problems in the same way that divorce in an unhappy marriage is not a solution to systemic problems.

The genre of tweet that Donegan references is a perfect encapsulation of hetero-exceptionalism: it implicitly or explicitly paints women’s romantic and sexual unhappiness as a personal failure. That is the water in which we swim. So much hetero dating advice for women ultimately reads as instructions for personally navigating patriarchy.

Granted, romantic and sexual unhappiness is not always accurately or exclusively blamed on inequality and heteronormativity. As a thought experiment, take those out of the equation. Love, intimacy, friendship, and sex are still tricky as hell. Finding your person or your people is hard. It can be lonely and maddening and full of missteps. But all of those things are infinitely trickier given gender inequality and heteronormativity. We live inside systems designed to breed disconnection and dependence.

I think the recent flood of “divorce books” has opened up all sorts of vital conversation among women who are married to men. I’ve certainly witnessed how these books—even their mere existence as an observed cultural phenomenon—can suddenly raise the privacy curtain that tends to drop once folks enter into heteronormative marriage (in contrast to the transparency between friends that often accompanies a period of dating and sleeping around in your twenties).

But I’ve also seen how these books can make married people feel a mix of defensive and accusatory. That is in part because, while these books are individual and specific, several also wrestle with systemic issues. Even if you’re happy in your marriage, you are likely to find something in these books that resonates, which is uncomfortable!

In some cases, there is instead a lack of resonance in these books, an extreme and outrageous contrast, which can breed a sense of superiority. That’s something Liars explicitly calls out in a meta fashion. Toward the end, once the protagonist has discovered her husband’s lying and cheating, she says: “I became the story that other married people got off on, murmuring together in bed, pitying me, loving [my husband] for making them look good, cherishing every disgusting detail.”1

As I’m imagining it, hetero-exceptionalism also relates to the stanning of Tim Walz and the Good Husband meme-ing of Doug Emhoff, which I recently wrote about as a desperate and grasping case of hetero-optimism that says, so very hopefully: Look how good men can be! Or could be, hypothetically! Mostly just based off of some cute TikTok compilation videos and random quotes from interviews where he comes off as a supportive spouse.

It’s worth noting: a couple days after I published the Emhoff piece, news broke that he had cheated on his first wife with a teacher at his children’s school, which—setting aside a more complicated conversation about how we mythologize monogamy—underscored the perils of investing hope for the hetero future in a single man. I think it’s important to avoid essentializing and naturalizing language about how men are, to hold out the highest hope for humanity and the capacity for intimate equality, while also acknowledging what the actual statistics say about how men are in the context of marriage and domesticity.

Love is often about exceptionalism. It’s about finding a special person who is unlike the rest. But the poison of hetero-exceptionalism is that it regards shitty husbands and bad boyfriends as personal and individual failings, even when the shitty and the bad arise from broader systemic forces that invade our most intimate relationships—all of them, to varying degrees.

The therapist Esther Perel says that the “shadow of the third” keeps monogamous couples together. The “third” could be a flirtatious coworker, an attractive stranger passed on the street, or even an engrossing personal hobby that in the best cases injects a sense of aliveness and mystery into the relationship, but also a sense of freedom and choice within the relationship.

I wonder about this other “shadow of the third” that follows many straight women: their sense of just how bad it is out there, in the dating scene or in other women’s marriages.

"I’m envisioning it as a variety of heteropessimism. It’s a perspective that recognizes that heteronormative love and sex can be punishing for women, while emphasizing exceptions (happy heteronormative relationships) that are attributed to men who are unicorns or women with discerning taste and romantic savvy. Crucially, it comes along with a sense of blame, specialness, and superiority, as opposed to solidarity."

Lots of things perfectly expressed here but this is one of my faves.

Ah, thank you! So glad that it resonated. 🧡